Laurie's Blogs.

Nov 2025

Spinal Walking in Cats: A Cornerstone of Locomotion Research

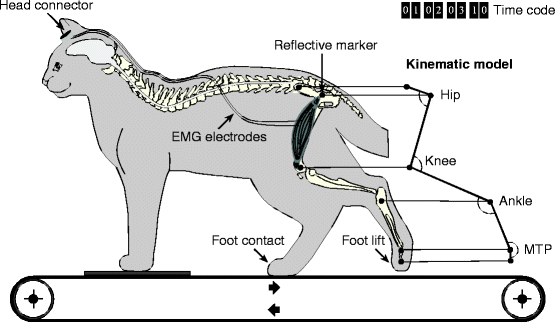

Picture from Frigon (2013)

If the recent buzz around spinal walking (SW) in dogs has you curious about its feline counterpart, you're in for a treat. While the dog study we chatted about earlier showed promising real-world rehab outcomes, cats have long been the gold standard in experimental research on SW. This involuntary, reflex-driven gait—powered by the spinal cord's central pattern generator (CPG)—emerged from decades of studies showing how even a "disconnected" spinal cord can relearn to walk. Let's break it down, drawing from key research, in a way that's actionable for your practice or lab work.

PS Grok did the heavy lifting to create this blog!

The Basics: What Is Spinal Walking in Cats?

Spinal walking in cats refers to the recovery of hindlimb locomotion after a complete spinal cord transection (typically at thoracic levels like T13), where brain-spinal connections are severed. Without supraspinal input, the lumbar CPG takes over, generating rhythmic stepping via interneurons and sensory feedback from the limbs. It's not voluntary—think reflex arcs syncing flexion and extension—but it can support full weight-bearing and precise foot placement with the right nudge.

This foundational research is rooted in the 1960s–70s when discoveries that spinalized cats could still "walk" on treadmills, challenging the idea that locomotion requires a intact brain-spinal highway. Fast-forward: Modern studies confirm SW as a model for neuroplasticity, where training and sensory cues "teach" the cord to adapt.

Key Research Highlights: From Bench to Breakthroughs

Cats' agility makes them ideal for dissecting SW mechanics. Here's a snapshot of pivotal findings:

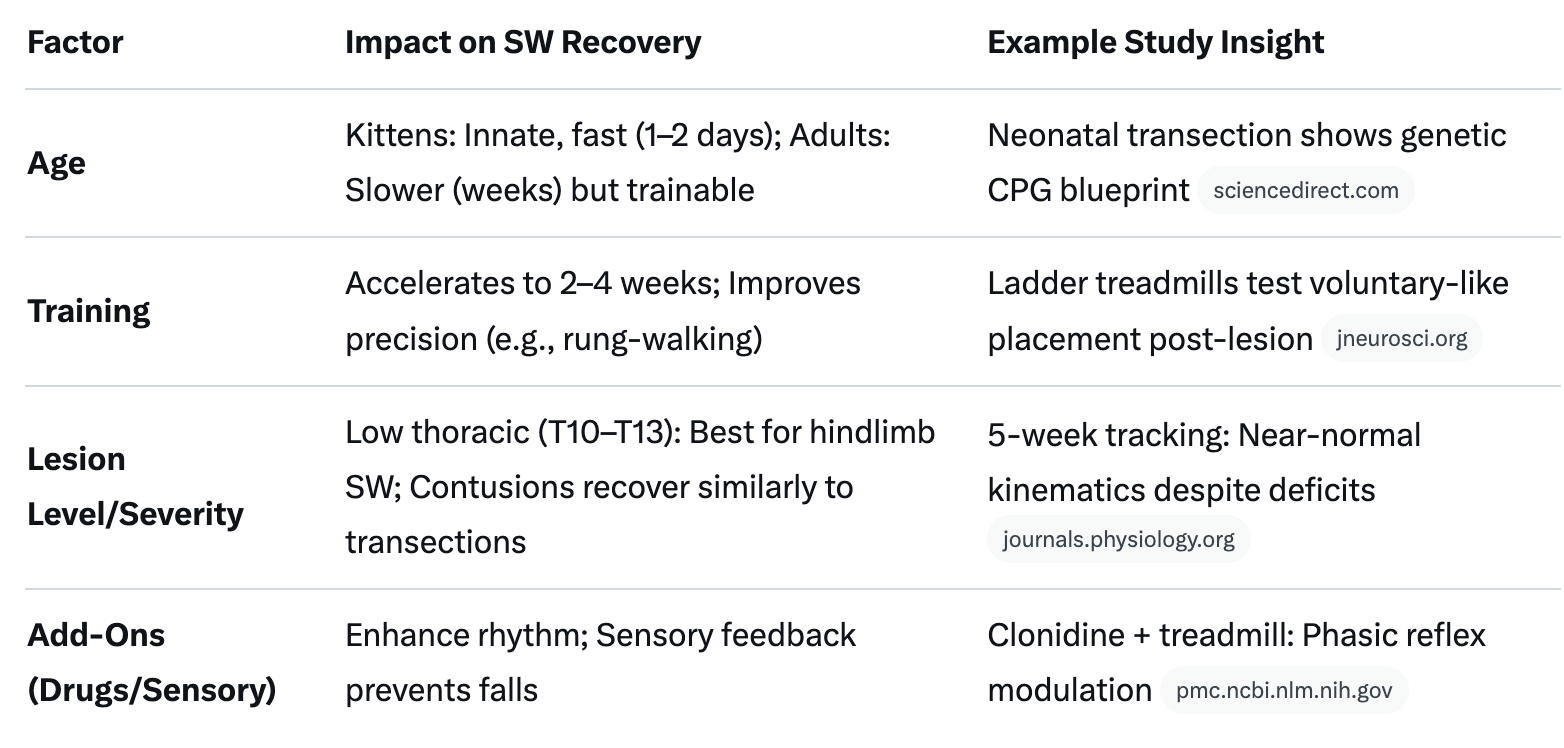

• Rapid Recovery in Kittens vs. Adults: Neonatally spinalized kittens (days old) can step within 1–2 days post-transection, thanks to innate CPG wiring—no "learning" needed. Adults take longer (3–12 weeks), but treadmill training slashes that to 2–4 weeks, yielding plantigrade steps and weight support. One classic setup: Forelimbs on a platform, hindlimbs on a belt—cats sync steps at human-like speeds (0.3–1 m/s).

• Training's Magic Touch: Untrained spinal cats drag paws or falter; trained ones? Full hindquarter support and adaptive responses to obstacles, like hole-stepping corrections. Protocols mix ground/underwater treadmills, electrostimulation, and kinesiotherapy. In a 2021 prospective study of nine cats with T13 injuries, 56% regained ambulation—44% via pure spinal walking—after 12 weeks of intensive rehab. Pro tip: Early sensory input (e.g., foot nerve zaps mimicking bumps) boosts interlimb coordination, hinting at why cats outperform rodents.

• Pharmacology and Plasticity Boosts: Drugs like clonidine (α-2 agonist) or serotonin agonists enhance extensor bursts, turning crude steps into fluid gait. Post-training, spinal circuits "rewire" load pathways for better stance support—fictive stepping (cord-generated rhythms under anesthesia) even modulates reflexes. Hemisection models (partial cuts) show asymmetric recovery, but full spinalization later reveals enduring spinal adaptations

Why Cats Matter (and How It Ties to Dogs & Humans)

Unlike dogs—where spinal walking is rarer in clinics (11% without rehab vs. 59% with intensive physio) from the dog paper—cats' experimental SW is robust, informing human trials like epidural stimulation for incomplete injuries. Their somatosensory tricks (e.g., limb coordination sans full brain input) could inspire feline rehab protocols, especially for trauma or IVDE cases. Imagine adapting cat-inspired treadmill rungs for cats—testing precision beyond flat belts.

Limitations? Most data's experimental (lab transections, not natural injuries), and trunk control's often assisted. Still, it's a plasticity powerhouse: Spinaizedl cats adapt to nerve transection, and can function on uneven terrain, suggesting rehab could harness this for real-world feline (or canine) paraplegia.

If you're treating spinalized small animals, start physio early… and hydrotherapy's a favourite for buoyancy-aided steps.

REFERENCES:

- Barrière G, Leblond H, Provencher J, Rossignol S. Prominent role of the spinal central pattern generator in the recovery of locomotion after partial spinal cord injuries. J Neurosci. 2008 Apr 9;28(15):3976-87.

- Battistuzzo, C. R., Callister, R. J., Callister, R., & Galea, M. P. (2012). A systematic review of exercise training to promote locomotor recovery in animal models of spinal cord injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 29(8), 1600–1613.

- Chau, C., Barbeau, H., & Rossignol, S. (1998). Early locomotor training with clonidine in spinal cats. Journal of Neurophysiology, 79(4), 2245–2257.

- de Leon, R. D., Hodgson, J. A., Roy, R. R., & Edgerton, V. R. (1998). Full weight-bearing hindlimb standing following stand training in the adult spinal cat. Journal of Neurophysiology, 80(1), 83–91.

- Edgerton, V. R., Tillakaratne, N. J. K., Bigbee, A. J., de Leon, R. D., & Roy, R. R. (2004). Plasticity of the spinal neural circuitry after injury. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 27, 145–167.

- Frigon, A., & Rossignol, S. (2006). Experiments and models of sensorimotor interactions during locomotion. Biological Cybernetics, 95(6), 607–627.

- Gallucci, A., Dragone, L., Menchetti, M., Gagliardo, T., Pietra, M., Cardinali, M., & Gandini, G. (2017). Acquisition of involuntary spinal locomotion (spinal walking) in dogs with irreversible thoracolumbar spinal cord lesion: 81 dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 31(2), 492–497.

- Lovely, R. G., Gregor, R. J., Roy, R. R., & Edgerton, V. R. (1986). Effects of training on the recovery of full-weight-bearing stepping in the adult spinal cat. Experimental Neurology, 92(2), 421–435.

- Martinez M, Delivet-Mongrain H, Leblond H, Rossignol S. Recovery of hindlimb locomotion after incomplete spinal cord injury in the cat involves spontaneous compensatory changes within the spinal locomotor circuitry. J Neurophysiol. 2011 Oct;106(4):1969-84.

- Musienko, P., Heutschi, J., Friedli, L., Van den Brand, R., & Courtine, G. (2012). Multi-system neurorehabilitative strategies to restore motor functions following severe spinal cord injury. Experimental Neurology, 235(1), 100–109.

- Rossignol, S., & Frigon, A. (2011). Recovery of locomotion after spinal cord injury: Some facts and mechanisms. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 34, 413–440.

- Smith, J. L., & Carlson-Kuhta, P. (1995). Development of locomotion in spinal kittens. In A. Wernig (Ed.), Plasticity of motoneuronal connections (pp. 131–149). Elsevier.

- Frigon, A. (2013). The Cat Model of Spinal Cord Injury. In: Aldskogius, H. (eds) Animal Models of Spinal Cord Repair. Neuromethods, vol 76. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ.