Laurie's Blogs.

Jan 2026

Canine Rib Tumors: Key Insights for Rehabilitation Practitioners

Last Saturday I saw 3 dogs, all with varying rib joint dysfunctions. Mobilizations yielded favourable results! So, in thinking about a blog topic, I thought I’d do a PubMed search to see if any new literature about canine rib joints and rib dysfunctions has hit the scientific waves. The answer to that question is, “Nope!” What PubMed kept showing me were articles about rib fractures and rib cancer. So, I figured, I’d dive into two papers that presented retrospective studies on rib cancer. It’s a topic I’ve not looked much into, so here goes!

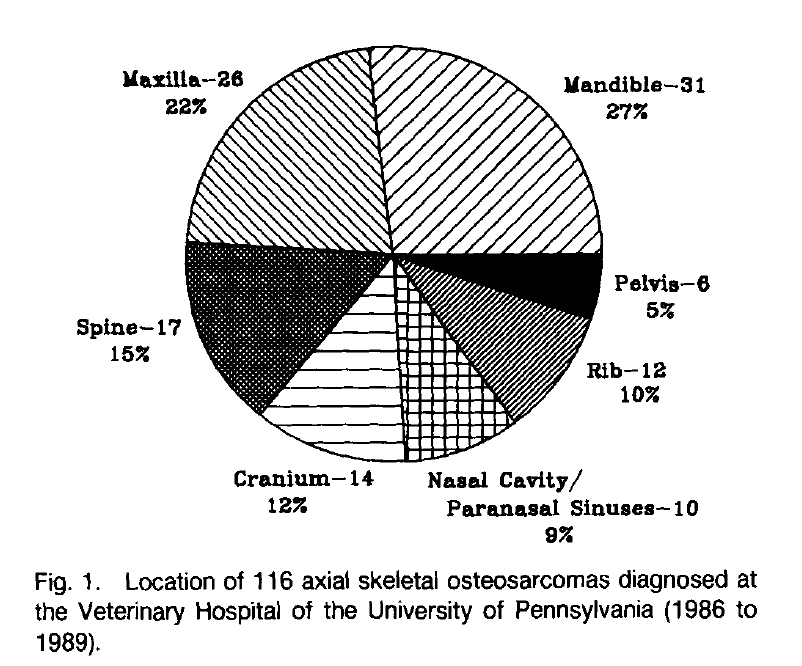

As canine rehabilitation practitioners, we should understand the nuances of rib tumours. This blog draws from two retrospective studies: Heyman et al. (1992) on axial skeletal osteosarcoma in 116 dogs (including 12 rib cases) and Pirkey-Ehrhart et al. (1995) on primary rib tumors in 54 dogs. Focus is placed on clinical presentation, disease progression, and life expectancy, with emphasis on osteosarcoma (OSA) and chondrosarcoma (CSA), the most common types.

Clinical Presentation

Rib tumors predominantly affect medium to large-breed dogs, with no strong breed predilection beyond overrepresentation in breeds like Golden Retrievers, German Shepherds, and Doberman Pinschers. In Heyman et al., rib OSA occurred in younger dogs (mean age 5.4 years) compared to other axial sites (overall mean 8.7 years). Pirkey-Ehrhart et al. reported median ages of 7 years for OSA and 6 years for CSA, with dogs over 20 kg comprising 83% of cases.

Common presenting signs include a palpable mass on the thoracic wall, often at the costochondral junction. Additional symptoms noted in Pirkey-Ehrhart et al. were weight loss (56%), lethargy (39%), lameness (22%), and dyspnea (4%). Heyman et al. reported preoperative signs lasting from days to 2 years (mean 10 weeks), with regional lymphadenopathy in 7% of cases overall. Thoracic radiographs may reveal pulmonary metastases in 11-29% of rib OSA cases at diagnosis.

Disease Progression

Rib tumors are aggressive, with progression varying by histologic type. OSA, comprising 63% of cases in Pirkey-Ehrhart et al. and all rib cases in Heyman et al., shows high local invasiveness and metastatic potential. Pulmonary metastases were detected in 28.6% of rib OSA cases at presentation (Heyman et al.), rising post-treatment. Local recurrence rates post-surgery reached 66.7% (Heyman et al.), often within 9 weeks, due to incomplete margins. Progression leads to complications like pain, bleeding, reluctance to eat, and respiratory issues.

CSA progresses more slowly, with lower metastatic rates; in Pirkey-Ehrhart et al., 53% of CSA dogs remained disease-free long-term, though pulmonary metastases eventually caused death in others. Hemangiosarcoma (HSA) and fibrosarcoma (FSA) exhibit rapid progression, with metastases or recurrence leading to euthanasia within months.

Factors influencing progression include incomplete surgical margins (5.6-fold increased risk of recurrence/death; Pirkey-Ehrhart et al.) and lack of adjuvant therapy for OSA. En bloc resection is standard, but reconstruction (e.g., polypropylene mesh) may cause short-term issues like edema or effusion, relevant for rehab planning.

Life Expectancy

Prognosis depends on tumor type and treatment. For rib OSA:

• Surgery alone: Median survival 90 days, disease-free interval (DFI) 60 days (Pirkey-Ehrhart et al.); aligns with Heyman et al.'s overall axial OSA median of 22 weeks (154 days).

• Surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy (cisplatin ± doxorubicin): Median survival 240 days, DFI 225 days (Pirkey-Ehrhart et al.), significantly better (p=0.024) than surgery alone.

CSA offers superior outcomes: Median survival and DFI both 1,080 days post-resection (Pirkey-Ehrhart et al.), with some dogs surviving >7 years.

HSA and FSA have poorer prognoses: Survival 30-210 days for HSA and 120-450 days for FSA, all ending in metastasis or recurrence.

No treatment yields short survival (median 15 days for OSA). Complete margins improve outcomes across types; age, weight, sex, tumor volume, and ribs resected do not significantly affect survival.

Implications for Rehabilitation

In rehab settings, one of our first priorities is to identify when a case is not a straight forward rehabilitation case (i.e. identify potential tumours and refer them back to their primary veterinarian for further diagnostics and care options). This paper can help us understand the clinical presentation of osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma, the most common types of rib cancers. The more you know, the more responsible of a clinician you become!

On that note, cheers until next time!

Laurie

References:

Heyman, S. J., Diefenderfer, D. L., Goldschmidt, M. H., & Newton, C. D. (1992). Canine axial skeletal osteosarcoma: A retrospective study of 116 cases (1986 to 1989). Veterinary Surgery, 21(4), 304–310.

Pirkey-Ehrhart, N., Withrow, S. J., Straw, R. C., Ehrhart, E. J., Page, R. L., Hottinger, H. L., Hahn, K. A., Morrison, W. B., Albrecht, M. R., Hedlund, C. S., Hammer, A. S., Holmberg, D. L., Moore, A. S., King, R. R., & Klausner, J. S. (1995). Primary rib tumors in 54 dogs. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 31(1), 65–69.